Bedford’s River Highway

The Great Ouse once bustled with cargo boats sailing to and from Bedford.

Can you imagine the river as it bustled with boats in the early 1800s? Cargoes included coal, grains, building materials, and supplies for local clothiers, metalworkers, brewers and bakers. Drains were cut to improve riverside pastures. Illustration by Pete Urmston

Bedford opened to cargo boats in 1689, massively increasing trade opportunities and reducing transport costs, for boats could carry ‘as much with one horse as Carters do with 40’. The newly dredged waterways offered smoother, more reliable transport than notoriously poor local roads.

Common local exports included corn, oats, barley, rye, malt, peas, beans, flour, flax and hemp seeds. Imports included salt, fish, and reeds or sedge for thatching buildings. Trade records note also clay for tobacco pipes, fuller’s earth for use in the woollens industries, iron, turfs, pitch, tar, oil, pots, pigeon dung for fertiliser and building materials.

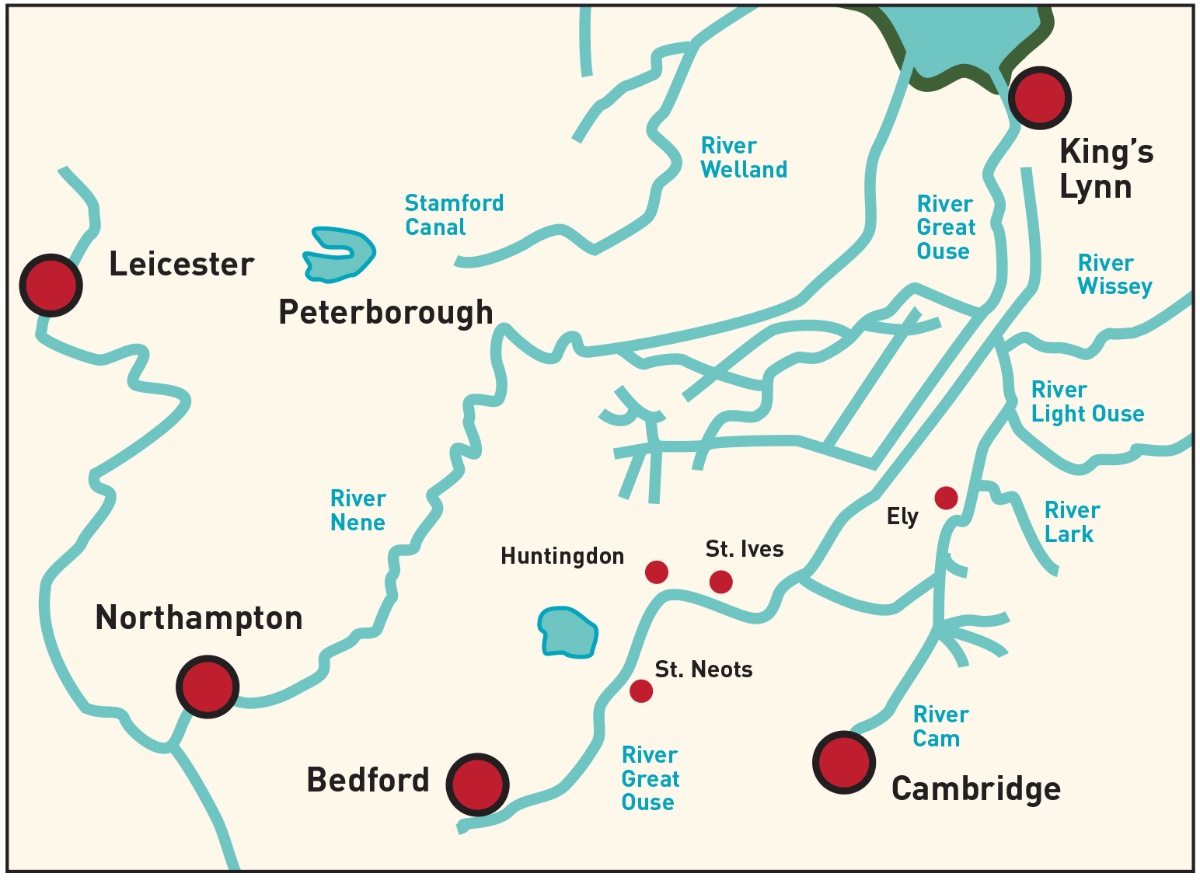

Coals from Newcastle

The River Ouse connected Bedford to other major rivers and towns as well as King’s Lynn seaport, which handled coal from Newcastle.

The River Ouse linked Bedford with King’s Lynn, an important east coast seaport dealing in coal from Tyneside, and goods to and from London. Bedford became the centre of local coal trading.

Transport costs and taxes created startling price hikes. The St Ives to Bedford stretch alone cost about 3s 6d per ton in tolls throughout the 1700s and 1800s. Records from the early 1700s show coal bought at 11 shillings 6 pence per chaldron in Newcastle, cost 25s at King’s Lynn, and sold for up to 40s per chaldron at Bedford.

Navigation was seasonal. Wily dealers stored up coals in the summer, against poor travel prospects and increased prices in winter. In 1853 the Bedford Gas Company urged an immediate delivery of coal, being in ‘much doubt as to Navigation being passable much longer’. Whether boat crews took alternative winter jobs, or saved up through summer, we don’t know.

Boats and Boat Crews

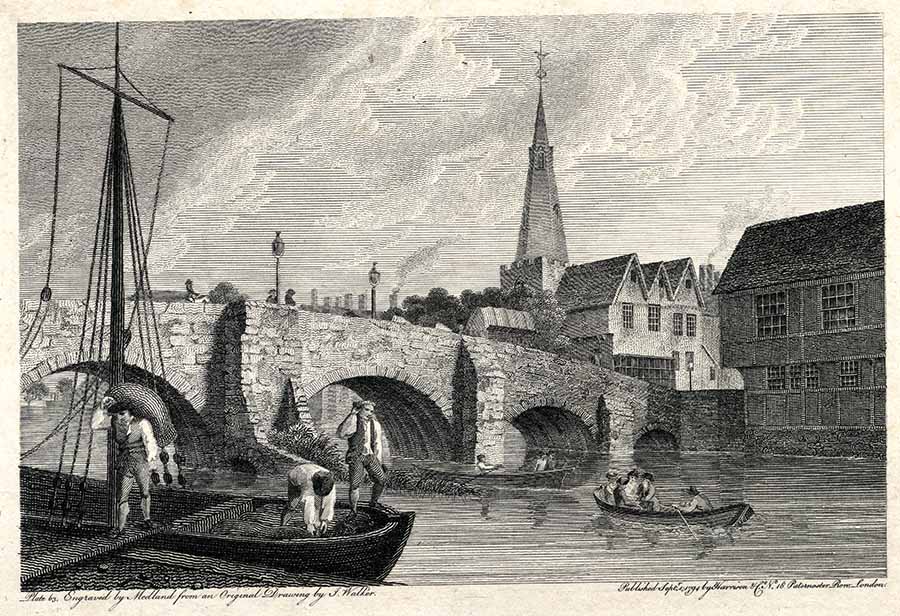

River traffic by the old Bedford town bridge, 1794. Some residents complained of the river being too full of boats for fishing! Photograph courtesy of Bedfordshire and Luton Archives Service.

Narrow Fenland lighters were the main local cargo boats, measuring about 48 feet long. Crews had two specialisms. Watermen skilfully navigated the Ouse’s challenging shallows. Horsemen managed the towing horses. Great Ouse boatmen reputedly had ‘a greater fund of bad language than any other waterway in England’. It was thirsty work and the crews had favourite pubs along the way, including the Ship at Bedford.

Flat-bottomed Humber keels also suited the shallow waterways. The Bedford Levels Corporation passed laws on the minimum height of river bridges to accommodate their 50-foot masts.

Packets, or passenger boats, paid a levy of 1d per passenger. By the mid 1820s steam packets offered faster journeys than traditional horse packets.

Dig Deeper

Watch a Humber keel under sail off the coast of Lincolnshire.

A Controversial Development

Local tanner, Henry Ashley Snr, was first to open the stretch of river to Bedford, as he looked to maximise returns on his £160 per annum payment for local Navigation rights. But he was not without opposition!

Some local landowners feared river tolls would increase corn prices to the consumer, and so depress the market for their corn, in turn lowering the rents they could charge for their land.

Others would have preferred to drain local land to increase cattle and dairy production.

Millers feared the loss of water power to power their mills. One protest claimed millers might ‘lose 20s a day for want of Water to Grind, and the Millers forced to work on Sundays to please their customers.’

From Water to Rail

The ongoing tensions came to an abrupt end with the advent of the Varsity Railway in 1862, as steam trains rapidly replaced boats as the business transport of choice.

Visit

Follow National Cycle Route 51 from Priory Country Park to the Grange Estate, near Willington, from where a new 1.8 mile cycle trail has been created that will take you around the Estate and close to the River Great Ouse, before bringing you back to Route 51.